When Considering A Practice Change, Why Is Identification Of Stakeholders Important?

- Inquiry

- Open up Access

- Published:

A comparison of policy and direct practise stakeholder perceptions of factors affecting evidence-based practice implementation using concept mapping

Implementation Science volume 6, Article number:104 (2011) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Background

The goal of this study was to assess potential differences between administrators/policymakers and those involved in direct practice regarding factors believed to exist barriers or facilitating factors to evidence-based practice (EBP) implementation in a large public mental health service system in the United states of america.

Methods

Participants included mental health organization county officials, bureau directors, plan managers, clinical staff, administrative staff, and consumers. As part of concept mapping procedures, brainstorming groups were conducted with each target grouping to identify specific factors believed to be barriers or facilitating factors to EBP implementation in a large public mental health system. Statements were sorted by similarity and rated by each participant in regard to their perceived importance and changeability. Multidimensional scaling, cluster analysis, descriptive statistics and t-tests were used to analyze the data.

Results

A total of 105 statements were distilled into 14 clusters using concept-mapping procedures. Perceptions of importance of factors affecting EBP implementation varied between the two groups, with those involved in straight exercise assigning significantly higher ratings to the importance of Clinical Perceptions and the touch of EBP implementation on clinical practice. Consistent with previous studies, financial concerns (costs, funding) were rated among the about important and to the lowest degree likely to change by both groups.

Conclusions

EBP implementation is a complex procedure, and different stakeholders may concord different opinions regarding the relative importance of the bear on of EBP implementation. Implementation efforts must include input from stakeholders at multiple levels to bring divergent and convergent perspectives to calorie-free.

Background

The implementation of evidence-based practices (EBPs) into existent-world children's mental health service settings is an important step in improving the quality of services and outcomes for youth and families [1, 2]. This holds especially true for clients in the public sector who oft have difficulty accessing services and have few alternatives if treatments are not effective. Public mental wellness services are embedded in local health and human being service systems; therefore, input from multiple levels of stakeholders must exist considered for constructive major modify efforts such equally implementation of EBP [3, iv]. In public mental healthcare, stakeholders include not only the individuals about directly involved--the consumers, clinicians, and administrative staff--but also program managers, agency directors, and local, state, and federal policymakers who may structure organizations and financing in ways more or less conducive to EBPs.

Considerable resource are being used to increase the implementation of EBPs into community care; however, bodily implementation requires consideration of multiple stakeholder groups and the different ways they may be impacted. Our conceptual model of EBP implementation in public sector services identifies four phases of implementation--exploration, adoption determination/preparation, active implementation, and sustainment--and notes the importance of considering the interests of multiple levels of stakeholders during each phase to result in positive sustained implementation [5]. Similarly, Grol et al. suggest that those implementing innovations such as new guidelines and EBPs in medical settings should consider multiple levels and contexts including the innovation itself, the private professional, the patient, the social context, the organizational context, and the economical and political context [6]. In society to address such implementation challenges, input from stakeholders representing each level (patient, provider, organization, political) must be considered every bit part of the overall implementation context.

Stakeholders that view service change from the policy, organisation, and organizational perspectives may have dissimilar views than those from clinical and consumer groups regarding what is important in EBP implementation. For example, at the policy level, bureaucratic structures and processes influence funding and contractual agreements between governmental/funding agencies and provider agencies [seven]. Challenges in administering twenty-four hour period-to-day operations of clinics, including leadership abilities, high staff turnover, and need for adequate training and clinical supervision may serve every bit barriers or facilitators to the implementation of EBPs [eight]. At the practise level, providers contend with high caseloads, meeting the needs of a variety of clients and their families, and relationships with peers and supervisors [9], while consumers bring their own needs, preferences, and expectations [x]. This characterization, while overly simplified, illustrates how challenges at multiple levels of stakeholders tin can impact the implementation of EBPs. Some accept speculated that 1 reason why implementation of EBP into everyday do has not happened is the challenge of satisfying such various stakeholder groups that may hold very different values and priorities [11, 12]. In order to better identify what factors may exist important during implementation, it is essential to understand the perspectives of unlike stakeholder groups including areas of convergence and divergence.

Efforts to implement EBPs should exist guided past knowledge, evidence, and experience regarding constructive system, organizational, and service change efforts. Although there is growing interest in identifying key factors probable to affect implementation of EBPs [13–17], much of the existing evidence is from outside the US [18–twenty] or outside of healthcare settings [21, 22]. With regard to implementation of evidence and guidelines in medical settings, systematic reviews take shown that strategies that take into business relationship factors relating to the target group (eastward.g., knowledge and attitudes), to the arrangement (e.g., chapters, resources, and service abilities), and to reinforcement from others have the greatest likelihood of facilitating successful implementation [6, 23, 24].

Additionally, research on implementation of innovations, such as implementing a new EBP, suggests that several major categories of factors may serve equally facilitators or barriers to change. For example, changes are more likely to be implemented if they take demonstrated benefits (eastward.g., competitive advantage) [25]. Conversely, higher perceived costs discourage change [25, 26]. Change is also more than likely to occur and persist if it fits the existing norms and processes of an organization [27–29]. Organizational civilisation can impact how readily new technologies will exist considered and adopted in practice [30], and there is concern that some public sector service organizations may have cultures that are resistant to innovation [3, 31]. The presence of supportive resources and leadership likewise make alter much more probable to occur inside organizations [32]. On an individual level, change is more than likely when individuals believe that implementing a new practice is in their best interest [25, 32]. While these studies provide a framework for exploring barriers and facilitating factors to implementation of innovation, most are from settings where factors may be very different than in customs-based mental health agencies and public sector services [18, xix]. Thus, there are likely to be both common and unique factors in conceptual models from different types of systems and organizations.

While there is generally a dearth of enquiry examining barriers and facilitating factors to implementation of EBPs across multiple service systems, one enquiry team has utilized observation and interview methods to examine barriers and facilitating factors to successful implementation for two specific EBPs in multiple community mental health centers [33, 34]. The investigators found iii significant common barriers emerged across v implementation sites: deficits in skills and role performance by front-line supervisors, resistance by front-line practitioners, and failure of other bureau personnel to adequately fulfill new responsibilities [33]. While barriers such as funding and height level administrative support were common barriers, addressing them was not plenty to produce successful implementation, and propose that a 'synergy' needs to exist involving upper-level administration, plan leaders, supervisors, direct services workers, and related professionals in the organization to produce successful EBP implementation in community mental wellness settings [33]. Additionally, the authors' qualitative findings pointed to a number of facilitating factors for successful implementation across sites, including the use of fidelity monitoring, potent leadership, focused squad meetings, mentoring, modeling, and high-quality supervision [34].

Across studies in mental health, medical, and organizational settings, a number of mutual implementation barriers and facilitating factors occurring at multiple stakeholder levels have been identified. Nevertheless, despite show pointing to the need to consider implementation factors at multiple levels, at that place is a lack of enquiry examining perspectives of implementation barriers and facilitating factors among those at different stakeholder levels. The overall purpose of the current study is to examine divergent and convergent perspectives towards EBP implementation between those involved in creating and carrying out policy and procedures and those involved in direct practice. Previous enquiry has indicated a need to include multiple perspectives when implementing new programs and policies, merely provided few guidelines regarding how to succinctly capture diverse perspectives. The current study uses concept mapping to both appraise the level of agreement between policy and direct practice groups with regard to factors important for EBP implementation, and suggests ways to incorporate multiple perspectives into a conceptual framework to facilitate successful implementation.

Methods

Written report context

The written report took place in San Diego County, the sixth almost populous county in the United States (at the fourth dimension of the study). San Diego County is very diverse, comprised of 51% Non-Hispanic Caucasian, 30% Latino, 5% Black, 10% Asian, and iv% other racial/ethnic groups [35]. The canton youth mental health system supports over 100 mental health programs. Funding for these programs primarily comes from state allocated mental health dollars provided to and administered by each county. Other sources of funding include public and individual insurance. The majority of services are provided through canton contracts to community-based organizations, although the county as well provides some directly services using their own staff.

Participants

Participants included 31 stakeholders representing diverse mental health service system organizational levels and a broad range of mental wellness agencies and programs, including outpatient, mean solar day treatment, case direction, and residential services. Participants were recruited based on the investigative team's in-depth knowledge of the service system with input from system and organizational participants. Offset, county children'southward mental wellness officials were recruited for participation by the research team. These officials worked with the investigators to place agency directors and program managers representing a broad range of children and family mental wellness agencies and programs, including outpatient, day treatment, case management, and residential. There were no exclusion criteria. The investigative team contacted agency directors and program managers by email and/or phone to describe the report and request their participation. Recruited program managers so identified clinicians, administrative support staff, and consumers for projection recruitment. Canton mental health directors, bureau directors, and plan managers represent the policy interests of implementation, while clinicians, administrative support staff, and consumers were recruited to represent the direct practice perspectives of EBP implementation. Demographic data including age, race/ethnicity, and gender was collected on all participants. Data on educational background, years working in mental wellness, and experience implementing EBPs was nerveless from all participants except consumers.

Study design

This projection used concept mapping, a mixed methods arroyo with qualitative procedures used to generate information that can and so be analyzed using quantitative methods. Concept mapping is a systems method that enables a group to describe its ideas on any topic and represent these ideas visually in a map [36]. The method has been used in a wide range of fields, including health services enquiry and public health [14, 37, 38].

Procedure

Start, investigators met with a mixed (across levels) group of stakeholder participants and explained that the goal of the project was to identify barriers and facilitators of EBP implementation in public sector child and adolescent mental health settings. They then cited and described 3 specific examples of EBPs representing the most common types of interventions that might be implemented (east.yard., private kid-focused (cerebral problem solving skills training), family-focused (functional family unit therapy), and group-based (aggression replacement grooming)). In improver to a clarification of the interventions, participants were provided a written summary of training requirements, intervention duration and frequency, therapist experience/didactics requirements, cost estimates, and price/benefit estimates. The investigative squad then worked with the study participants to develop the following 'focus statement' to guide the brainstorming sessions: ' What are the factors that influence the acceptance and use of evidence-based practices in publicly funded mental health programs for families and children?'

Brainstorming sessions were conducted separately with each stakeholder group (canton officials, agency directors, program managers, clinicians, authoritative staff, and consumers) in order to promote candid response and reduce desirability effects. In response to the focus statement, participants were asked to brainstorm and identify concise statements that described a single concern related to implementing EBP in the youth mental health service system. Participants were also provided with the three examples of EBPs and the associated handouts described in a higher place to provide them with easily accessible data about common types of EBPs and their features. Statements were collected from each of the brainstorming sessions, and duplicates statements were eliminated or combined by the investigative squad to dribble the list into distinct statements. Statements were randomly reordered to minimize priming furnishings. Researchers met individually with each written report participant, gave them a pile of cards representing each distinct statement (one statement per card), and asked each participant to sort like statements into the aforementioned pile, yielding every bit many piles equally the participant deemed advisable. Finally, each participant was asked to charge per unit each statement describing what influences the acceptance and employ of EBPs in publicly funded mental wellness programs on a 0 to 4 indicate scale on 'importance' (from 0 'not at all important' to 4 'extremely important') and 'changeability' (from 0 'non at all changeable' to iv 'extremely child-bearing') based on the questions, 'How of import is this cistron to the implementation of EBP?' and 'How child-bearing is this factor?'

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using concept mapping procedures incorporating multidimensional scaling (MDS) and hierarchical cluster assay in order to group items and concepts and generate a visual display of how items clustered across all participants. Data from the card sort described to a higher place were entered into the Concept Systems software [39], which places the information into a square symmetric similarity matrix [xl]. A similarity matrix is created by arranging each participant'southward card sort data in rows and columns denoting whether or non they placed each pair of statements in the same category. For example, a 'one' is placed in row iii, cavalcade ane if someone put statements 1 and three in the same pile indicating those cards were judged as similar. Cards not sorted together received a '0.' Matrices for all subjects are and so summed yielding an overall square symmetric similarity matrix for the entire sample. Thus, whatever prison cell in this matrix can have integer values betwixt 0 and the total number of people who sorted the statements; the value of each prison cell indicates the number of people who placed each pair in the same pile. The square symmetric similarity matrix is analyzed using MDS to create a ii dimensional 'point map,' or a visual representation of each argument and the altitude betwixt them based on the square symmetric similarity matrix. Each argument is represented as a numbered point, with points closest together more conceptually similar. The stress value of the point map is a measure of how well the MDS solution maps the original data, indicating good fit. The value should range from 0.ten to 0.35, with lower values indicating a better fit [39]. When the MDS does not fit the original information (i.e., the stress value is too high), it means that the distances of statements on the point map are more than discrepant from the values in the foursquare symmetrical similarity matrix. When the data maps the solution well, information technology means that distances on the point map are the aforementioned or very similar to those from the square symmetrical similarity matrix.

Cluster analysis is then conducted based on the square symmetric similarity matrix information that was utilized for the MDS analysis in order to delineate clusters of statements that are conceptually like. An associated cluster map using the grouping of statements is created based on the point map. To determine the terminal cluster solution, the investigators evaluated potential cluster solutions (e.grand., 12 clusters, 15 clusters) and and then agreed on the final model based on interpretability. Interpretability was determined when consensus was reached amidst three investigators that creating an additional cluster (i.eastward., going from 14 to fifteen cluster groupings) would not increase the meaningfulness of the data. Next, all initial report participants were invited to participate with the enquiry squad in defining the meaning of each cluster and identifying an advisable name for each of the final clusters.

Cluster ratings for 'importance' were computed for both the policy and directly do groups and displayed on divide cluster rating maps. Additionally, cluster ratings for 'changeability' were computed for both the policy and direct practice groups. Overall cluster ratings, represented past layers on the cluster rating map, are really a double averaging, representing the boilerplate of the mean participant ratings for each argument beyond all statements in each cluster, so that one value represents each cluster'southward rating level. Therefore, even seemingly slight differences in averages between clusters are likely to be meaningfully interpretable [41]. T-tests were performed to examine differences in mean cluster ratings of both importance and changeability between the policy and directly practice groups, with outcome sizes calculated using Cohen's d[42].

As part of the concept-mapping procedures, blueprint matching was completed to examine the relationships between ratings of importance and ratings of changeability for the policy and straight practice groups. Blueprint matching is a bivariate comparison of the cluster average ratings for either multiple types of raters or multiple types of ratings. Pattern matching allows for the quantification of the relationship between two sets of interval level ratings aggregated at the cluster level past providing a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, with higher correlations indicating greater congruence. In the electric current project, we created 4 pattern matches. First, we conducted i blueprint match comparison cluster average ratings on importance between the policy and direct practice groups. Side by side, we conducted a second analysis comparing cluster boilerplate ratings on changeability between the policy and direct practise groups. Finally, pattern matching was used to depict the relationships between cluster importance ratings and cluster changeability ratings for the policy group and the straight exercise group.

Results

Sample characteristics

The policy group (Northward = 17) consisted of 5 county mental health officials, v bureau directors, and 7 program managers. The direct practice grouping (N = 14) consisted of vi clinicians, three administrative support staff, and 5 mental wellness service consumers (i.e., parents with children receiving services). The majority of the participants were women (61.3%) and ages ranged from 27 to threescore years, with a mean of 44.iv years (SD = x.ix). For the direct practise group, 79% of the sample were female and the average age was 38.07 years (SD = 10.8), while the policy grouping contained just 47% females and had an boilerplate age of 49.60 years (SD = viii.threescore). The overall sample was 74.ii% Caucasian, nine.7% Hispanic, 3.ii% African American, 3.2% Asian American, and 9.7% 'Other.' A majority of participants had earned a Chief's degree or higher and most 3-quarters of non-consumer participants had direct experience implementing an EBP. The viii agencies represented in this sample were either operated past or contracted with the county. Agencies ranged in size from 65 to 850 full-fourth dimension equivalent staff and 9 to 90 programs, with the bulk located in an urban setting.

Statement generation and carte du jour sort

Thirteen participants representing all stakeholder types were available to work with the enquiry team in creating the focus statement. Brainstorming sessions with each of the stakeholder groups occurred separately and were approximately 1 hour in length (Chiliad = 59.5, SD = 16.2). From the brainstorming sessions, a total of 230 statements were generated across the stakeholder groups. By eliminating duplicate statements or combining similar statements, the investigative team so distilled these into 105 distinct statements. The participants sorted the bill of fare statements into an boilerplate of 11 piles (Grand = x.7, SD = iv.iii). The boilerplate fourth dimension it took to sort the statements was 35 minutes, and an additional 25 minutes for statement ratings.

Cluster map creation

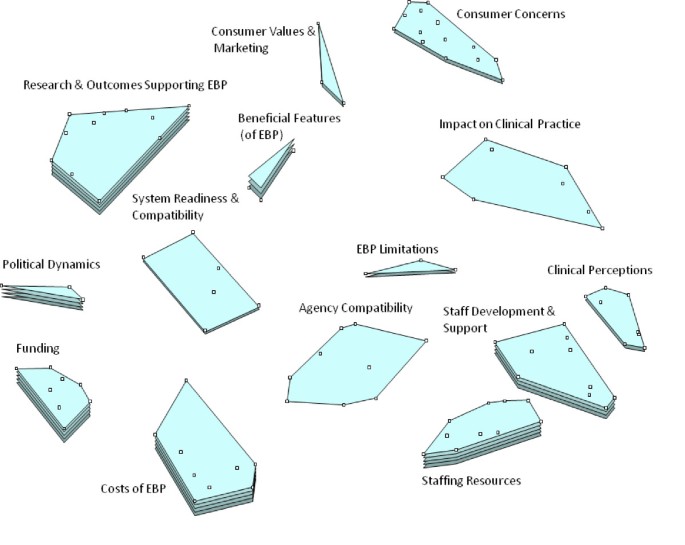

The stress value for the MDS analysis of the carte sort information was adequate at 0.26, which falls within the average range of 0.10 and 0.35 for concept-mapping projects. After the MDS analysis determined the bespeak location for statements from the card sort, hierarchical cluster analysis was used to segmentation the bespeak locations into not-overlapping clusters. Using the concept systems software, a team of three investigators independently examined cluster solutions, and through consensus determined a 14-cluster solution all-time represented the data.

Cluster descriptions

20-2 of the 31 initial written report participants (17 through consensus in a single group meeting and v through individual phone calls) participated with the research team in defining the pregnant of each cluster and identifying an appropriate proper name for each of the 14 final clusters. The clusters included: Clinical Perceptions, Staff Development and Support, Staffing Resources, Bureau Compatibility, EBP Limitations, Consumer Concerns, Impact On Clinical Practice, Benign Features (of EBP), Consumer Values and Marketing, Organisation Readiness and Compatibility, Research and Outcomes Supporting EBP, Political Dynamics, Funding, and Costs of EBP (statements for each cluster tin be constitute in Additional File 1). In order to provide for broad comparability, we use the overall cluster solution and examine differences in importance and changeability ratings for the policy and practice subgroups. Below, we will draw the general themes presented in each of the fourteen clusters nether analysis.

The 'Clinical Perceptions' cluster contains eight statements related to concerns about the role of an EBP therapist, including devaluation, fit with theoretical orientations, and limitations on creativity and flexibility, every bit well every bit positive factors such as openness, opportunities to learn skills, and motivations to aid clients. The ten statements in the 'Staff Development and Back up' cluster correspond items thought to facilitate implementation, such as having a staff 'champion' for EBP, having open and adaptable staff who accept buy in and are committed to the implementation, and having support and supervision available to clinicians, equally well every bit concerns such as required staff competence levels and abilities to learn EBP skills and staff concerns about evaluations and performance reviews. The three items in the 'Staffing Resources' cluster represent themes relating to competing demands on fourth dimension, finances, and free energy of staff and the challenges of irresolute staffing structure and requirements needed to implement EBP. The 9 items in the 'Agency Compatibility' cluster include themes relating to the fit of EBP with the bureau values, structure, requirements, philosophy, and information arrangement, as well equally the agencies commitment to education, inquiry, and ensuring fidelity and previous feel implementing EBPs. The 'EBP Limitations' cluster contains iii items relating to concerns of EBPs, including how they fit into electric current models, limitations on the number of clients served, and longer treatment length. The 'Consumer Concerns' cluster contains 14 items that relate to factors that would encourage EBP utilize among consumers, such every bit increased hope for improved results, decreased stigma associated with mental illness when using EBPs, and a fit of the EBP with consumers' culture, comfort, preference, and needs, likewise as concerns for consumers, such as expectations for a 'quick gear up,' resistance to interventions other than medications, and consumer apprehension about EBPs being seen every bit 'experiments.' The 'Impact On Clinical Practice' cluster contains viii items related to concerns well-nigh how EBP affects the therapeutic relationship, consistency of care, and the ability to individualize treatment plans for clinicians, every bit well every bit important characteristics of EBP implementation among clinicians, such as the ability to get a right diagnosis and the flexibility of EBPs to address multiple client issues and cadre issues. The 'Beneficial Features (of EBP)' cluster contains three items relating to important features of EBP, including its effectiveness for difficult cases, potential for adaptation without effecting outcomes, and the increased advocacy for its use. The 'Consumer Values and Marketing' cluster contains three items related to the EBP fit with values of consumer involvement and with consumers demand for measureable outcomes, as well equally the marketing of EBPs to consumers. The 'System Readiness and Compatibility' cluster contains six items relating to the ability of the service systems to support EBP, including purchase in of referral and organisation partners, equally well as the compatibility of EBP with other initiatives being implemented. The 'Research and Outcomes Supporting EBP' cluster contains xi statements relating to the proven effectiveness and sustainability of EBP service in real piece of work services, also as the ability of EBPs to mensurate outcomes for the system. The 'Political Dynamics' cluster contains three items relating to the political fairness in selecting programs, support for implementation of EBPs, and concerns of how multi-sector involvement may work with EBPs. The viii items in the 'Funding' cluster include themes related to the willingness of funding sources to adjust requirements related to productivity, caseloads, and express time frames to run across the requirements of EBPs, as well every bit a demand for funders to provide clearer contracts and requirements for EBPs. Finally, the 'Costs of EBP' cluster contains 9 items relating to concerns regarding the costs of training, equipment, supplies, administrative demands, and hidden costs associated with EBP implementation, besides as strengths of EBPs, such as being billable and providing a competitive reward for funding. Each of the statements contained in each cluster tin be considered a barrier or facilitating factor depending on the manner in which it is addressed. For case, the items related to willingness of funding sources to suit requirements to fit with the EBP can exist considered a barrier to the extent that funding sources fail to adjust to encounter the needs of the EBP or a facilitating factor when the funding source is prepared and adjusts accordingly to meet the needs and requirements of EBPs.

Cluster ratings

Figures 1 and 2 show the cluster rating maps for barriers and facilitators of EBP implementation separately for the policy group and practice group participants. In each figure, the number of layers in each cluster'south stack indicates the relative level of importance participants ascribed to factors within that cluster. A smaller cluster indicates that statements were more than oftentimes sorted into the same piles past participants (indicating a higher degree of similarity). Proximity of clusters to each other indicates that clusters are more related to nearby clusters than clusters further away. Overall orientation of the cluster-rating map (e.thou., top, bottom, right, or left) does not take any inherent meaning.

Policy stakeholder importance cluster rating map.

Practice stakeholder importance cluster rating map.

Tables 1 and ii present the mean policy and practice group ratings for each cluster, the ranking order of the cluster, and the related t-test and Cohen's event size (d) statistics for perceived importance and changeability (respectively). Only 2 clusters of the fourteen clusters were rated significantly different from each other in importance between the two groups. These significant differences occurred on the 'Impact On Clinical Practice' (d = 1.33) and 'Clinical Perceptions' (d = 0.69) clusters, where the directly practice group rated the clusters as significantly more important than those in groups that had oversight of policies and procedures. Additionally, t-tests of mean differences among the 14 clusters simply indicated significant differences in changeability ratings between the groups for financial factors, with the policy group rating them significantly less changeable.

Design matching

Design matching was used to examine bivariate comparison of the cluster average ratings. Peasons's product moment correlation coefficients indicate the degree to which the groups converge or diverge in perceptions of importance and changeability. In general, agreement between the ii groups regarding the cluster importance ratings (r = 0.44) was axiomatic. When ranking in order or importance ratings, v of the highest ranked six clusters were rated similarly in importance for the two groups (Funding, Costs of EBP, Staffing Resource, Research and Outcomes Supporting EBP, and Staff Evolution and Back up). At that place was also concordance between the to the lowest degree important factors with System Readiness and Compatibility, Agency Compatibility, and Limitations of EBP all falling in the bottom four rankings for both groups. Results from the pattern matching of changeability ratings revealed few differences between the ii groups for the fourteen domains as indicated by the high between-groups correlation (r = 0.78). Clinical Perceptions were rated most amenable to change in both the policy (1000 = two.69) and do groups (M = 2.71).

Pattern matching was also used to describe the discrepancies betwixt cluster importance ratings and cluster changeability ratings for both the policy and do groups. In that location was a small positive correlation between importance ratings and changeability ratings for those involved in directly do (r = 0.xx) where high importance ratings were associated with college changeability ratings. Conversely, there was a negative correlation between importance and changeability for the policy group (r = -0.39) whereby those factors rated equally nearly important were less likely to be rated as amendable to change. Resource bug emerged in 2 singled-out dimensions: fiscal (Funding, Costs of EBPs) and human (Staffing Resources, Staff Development and Support), which were both rated among the highest levels of importance for both groups. Financial domains (Funding and Costs) were rated amongst the least amendable to change by both groups; however, Staff Development and Back up was rated every bit more changeable past both groups.

Discussion

The electric current study builds on our previous research in which we identified multiple factors probable to facilitate or be barriers to EBP implementation in public mental wellness services [fourteen]. In the present study, we extended findings to appraise differences in policy and practice stakeholder perspectives on what it takes to implement EBP. These include concerns about the force of the bear witness base, how agencies with very express financial and man resources can acquit the costs bellboy to changing therapeutic modalities, concerns nearly effects on clinical do, consumer concerns near quality and stigma, and potential brunt for new types of services. Each cluster or factor tin be considered a facilitator or barrier to EBP implementation to the degree that the problems are effectively addressed. For example, funding is a facilitator when sufficient to back up preparation, infrastructure, and fidelity monitoring, but would exist considered a barrier if not sufficient to meet these and other common problems for EBP implementation.

While there was a great bargain of agreement betwixt administrators/policymakers and those involved in direct do in regard to the virtually of import and least of import barriers and facilitating factors, there were also differences. In regard to areas of understanding, these results tin be used target and address areas of concern prior to implementation. For instance, resource availability (fiscal and staffing) appeared to exist especially salient for both those at the policy and do levels. Such services tin be under-funded and often contend with loftier staff turnover often averaging 25% per yr or more [43]. Funds for mental health and social services may face competing priorities of legislatures that may favor funding to cover other increasing costs such as Medicaid and prisons [44]. Such concerns must not be overlooked when implementing EBPs in public sector settings, and may be addressed past higher policy level initiatives that have the power to change factors that appear unalterable at the bureau and practitioner levels. Hence, we propose that it is necessary for both policy makers and those involved in direct practice to be consulted and involved in a collaborative way when designing strategies to implement EBPs.

Conversely, contrasting stakeholder grouping perceptions suggests that taking different perspectives into account can inform implementation process and potentially outcomes, because satisfying the needs of multiple stakeholders has been cited as one of the major barriers to successful implementation of EBPs [11, 12]. Differences across stakeholder groups in their perceptions of the importance and changeability of factors affecting EBPs point to the need for increased communication amidst stakeholders to help develop a more consummate understanding of what affects implementation. Tailoring content and commitment method of EBP and related implementation information for item stakeholders may promote more than positive attitudes toward implementation of change in service models. For example, highlighting positive personal experiences along with research results of EBP on clinical practise may be an constructive strategy for practitioners, administrative staff, and consumers; however, policy makers may be more swayed by presentations of long-term cost effectiveness data for EBPs.

Additionally, a better understanding of different stakeholder perspectives may lead to better collaboration among different levels of stakeholders to ameliorate services and service delivery. Besides often, processes are less than collaborative due to time pressures, meeting the demands of funders (e.g., federal, state), and the day-to-day work of providing mental health services. Processes for such egalitarian multiple stakeholders input can facilitate commutation between cultures of research and do [45].

The piece of work presented here also adds to the knowledge base and informs our developing conceptual model of implementation. This study fits with our conceptual model of implementation that acknowledges the importance of because system, organizational, and individual levels and the interests of multiple stakeholders during the four phases of implementation (exploration, adoption/preparation, active implementation, sustainment) [5]. The model notes that different priorities might be more or less relevant for different groups, and that if a collaborative process in which multiple stakeholder needs are addressed is employed, implementation decisions and planning volition be more likely to result in positive implementation outcomes [46].

While this written report was conducted in a public mental health arrangement, it is important to note that at that place are numerous commonalities across public service sectors that increase the likely generalizability of the findings presented here [5]. For instance, mental health, child welfare, and alcohol/drug service settings commonly operate with a central authority that sets policy and directs funding mechanisms such as requests for proposals and contracts for services. Depending on the context, these directives may emanate from land or county level government agencies or some combination of both (due east.g., state provides directives or regulations for county level apply of funds or services). In addition, mental health managers, clinicians, and consumers may as well be involved with child welfare and/or alcohol/drug services nether contracts or memorandums of understanding with agencies or organizations in other sectors. Indeed, it is not uncommon for consumers to be involved in services in more one sector [47]

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study should exist noted. First, the sample was derived from one public mental health system which may limit generalizability. Hence, different participants could have generated different statements and rated them differently in terms of their importance and changeability. However, San Diego is among the six most populous counties in the U.s. and has a high degree of racial and ethnic diversity. Thus, while not necessarily generalizable to all other settings, the present findings likely represent many issues and concerns that are at play in other service settings. Additionally, the sample size poses a limitation equally we were unable to appraise differences between specific stakeholder types (i.e., county officials versus program managers) because there is bereft power. By grouping participants into policy/administrators and those in directly exercise, we were able to create group sizes large enough to detect medium to large effect sizes. It would not take been feasible to recruit samples for each of six stakeholder groups large enough to detect significant differences using concept mapping procedures. We opted to include a greater array of stakeholder types at the price of larger stakeholder groups. Future studies may consider examining larger numbers of fewer stakeholder types (i.east., just county officials, programme directors, and clinicians) to brand comparisons among specific groups. Another limitation concerns self-report nature of the data collected, considering some take suggested that the identification of perceived barriers past practitioners are oftentimes part of a 'sense-making' strategy that may accept varied meanings in dissimilar organizational contexts and may not chronicle directly to actual practice [48, 49]. However, in the electric current study, the focus statement was structured so that participants would express their beliefs based on general experiences with EBP rather than 1 particular project, hence reducing the likelihood of post hoc sense making and increasing the generalizability. It should as well exist noted that participants could have identified different statements and rated them differently for specific EBP interventions.

Conclusions

Large (and minor, for that thing) implementation efforts require a great bargain of forethought and planning in addition to having appropriate structures and processes to back up ongoing instantiation and sustainment of EBPs in circuitous service systems. The findings from this study and our previous piece of work [5, 14] provide a lens through which implementation can be viewed. At that place are other models and approaches to be considered, which may be less or more comprehensive than the 1 presented here [xv–17]. Our chief message is that careful consideration of factors at multiple levels and of importance to multiple stakeholders should be explored, understood, and valued as part of the collaborative implementation process through the four implementation phases of exploration, adoption decision/planning, agile implementation, and sustainment [5].

There are many 'cultures' to be considered in EBP implementation. These include the cultures of government, policy, organization management, clinical services, and consumer needs and values. In order to be successful, the implementation process must acknowledge and value the needs, exigencies, and values present and agile across these strata. Such cultural exchange as described past Palinkas et al.[45] will become a long way toward improving EBP implementation process and outcomes.

References

-

Hoagwood Grand, Olin S: The NIMH design for change report: Inquiry priorities in child and boyish mental health. J Am Acad Kid Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002, 41: 760-767. x.1097/00004583-200207000-00006.

-

Jensen PS: Commentary: The next generation is overdue. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003, 42: 527-530. x.1097/01.CHI.0000046837.90931.A0.

-

Backer TE, David SL, Soucy GE: Reviewing the Behavioral Scientific discipline Cognition Base of operations on Technology Transfer (NIDA Enquiry Monograph 155, NIH Publication No. 95-4035). 1995, Rockville, Doctor: National Plant on Drug Abuse

-

Ferlie EB, Shortell SM: Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001, 79: 281-315. 10.1111/1468-0009.00206.

-

Aarons GA, Hurlburt Thousand, Horwitz Due south: Advancing a conceptual model of show-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011, 38: iv-23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-vii.

-

Grol R, Wensing M: What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving show-based exercise. Med J Aust. 2004, 180: S57-S60.

-

Glisson C: Structure and applied science in human service organizations. Human being services equally circuitous organizations. Edited by: Hasenfeld Y. 1992, Yard Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 184-202.

-

Lehman WEK, Greener JM, Simpson DD: Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Corruption Treat. 2002, 22: 197-209. 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00233-7.

-

Aarons GA: Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practise Attitude Calibration (EBPAS). Adm Policy Ment Health. 2004, 6: 61-74.

-

Laing A, Hogg G: Political exhortation, patient expectation and professional execution: Perspectives on the consumerization of wellness intendance. Brit J Manage. 2002, 13: 173-188. 10.1111/1467-8551.00230.

-

Hermann RC, Chan JA, Zazzali JL, Lerner D: Aligning measurement-based quality improvement with implementation of evidence-based practices. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006, 33: 636-645. 10.1007/s10488-006-0055-one.

-

Innvaer S, Vist Thou, Trommald Thou, Oxman A: Health policy-makers' perceptions of their utilise of evidence: a systematic review. J Wellness Serv Res Policy. 2002, 7: 239-244. x.1258/135581902320432778.

-

Aarons GA: Measuring provider attitudes toward evidence-based exercise: Consideration of organizational context and private differences. Kid Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005, 14: 255-271. ten.1016/j.chc.2004.04.008.

-

Aarons GA, Wells RS, Zagursky K, Fettes DL, Palinkas LA: Implementing bear witness-based practice in customs mental health agencies: A multiple stakeholder analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009, 99: 2087-2095. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161711.

-

Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh South, Alexander J, Lowery J: Fostering implementation of health services enquiry findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation scientific discipline. Implement Sci. 2009, 4: 50-10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

-

Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F: Implementation Research: A synthesis of the literature. 2005, Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Establish, The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publication #231)

-

Greenhalgh T, Robert K, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O: Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82: 581-629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x.

-

Dopson S, Fitzgerald 50: The function of the middle managing director in the implementation of show-based wellness care. J Nurs Manag. 2006, 14: 43-51. x.1111/j.1365-2934.2005.00612.x.

-

Dopson S, Locock L, Gabbay J, Ferlie E, Fitzgerald L: Prove-based medicine and the implementation gap. Health: An Interdisciplinary Periodical for the Social Report of Wellness, Illness and Medicine. 2003, 7: 311-330. 10.1177/1363459303007003004.

-

Morgenstern J: Effective engineering science transfer in alcoholism treatment. Subst Utilize Misuse. 2000, 35: 1659-1678. ten.3109/10826080009148236.

-

Frambach RT, Schillewaert N: Organizational innovation adoption: A multi-level framework of determinants and opportunities for future research. J Bus Res Special Issue: Marketing theory in the adjacent millennium. 2002, 55: 163-176.

-

Klein KJ, Conn AB, Sorra JS: Implementing computerized engineering: An organizational analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2001, 86: 811-824.

-

Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB: Changing physician performance: a systematic review of the event of standing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995, 274: 700-ten.1001/jama.274.9.700.

-

Solomon DH, Hashimoto H, Daltroy Fifty, Liang MH: Techniques to ameliorate physicians' use of diagnostic tests: a new conceptual framework. JAMA. 1998, 280: 2020-10.1001/jama.280.23.2020.

-

Buchanan D, Fitzgerald 50, Ketley D, Gollop R, Jones JL, Lamont SS, Neath A, Whitby East: No going back: A review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. Int J of Manage Rev. 2005, 7: 189-205. ten.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x.

-

Rimmer Thousand, Macneil J, Chenhall R, Langfield-Smith K, Watts Fifty: Reinventing Competitiveness: Achieving Best Practice in Australia. 1996, South Melbourne, Australia: Pitman

-

Kotter JP: Leading Alter: Why Transformation Efforts Neglect. (Cover story). Harvard Autobus Rev. 1995, 73: 59-67.

-

Lozeau D, Langley A, Denis J-L: The corruption of managerial techniques by organizations. Man Relations. 2002, 55: 537-564. x.1177/0018726702055005427.

-

Pettigrew AM, Ferlie E, McKee L: Shaping strategic change: Making alter in large organizations: The case of the National Health Service. 1992, London: Sage Publications

-

Hemmelgarn AL, Glisson C, Dukes D: Emergency room culture and the emotional support component of Family-Centered Care. Child Health Intendance. 2001, xxx: 93-110. ten.1207/S15326888CHC3002_2.

-

Diamond MA: Innovation and diffusion of applied science: A human process. Consult Psychol J. 1996, 48: 221-229.

-

Dale BG, Boaden RJ, Wilcox M, McQuater RE: Sustaining continuous improvement: What are the central problems?. Quality Engineering. 1999, 11: 369-377. 10.1080/08982119908919253.

-

Rapp CA, Etzel-Wise D, Marty D, Coffman M, Carlson L, Asher D, Callaghan J, Holter 1000: Barriers to testify-based practice implementation: results of a qualitative study. Community Ment Health J. 2010, 46: 112-118. 10.1007/s10597-009-9238-z.

-

Rapp CA, Etzel-Wise D, Marty D, Coffman One thousand, Carlson 50, Asher D, Callaghan J, Whitley R: Evidence based practice implementation strategies: Results of a qualitative study. Community Ment Health J. 2008, 44: 213-224. 10.1007/s10597-007-9109-4.

-

US Census Bureau: Land and county quick facts: San Diego County, California. 2010, US Census Bureau

-

Trochim WM: An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 1989, 12: one-sixteen. x.1016/0149-7189(89)90016-5.

-

Burke JG, O'Campo P, Tiptop GL, Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Trochim WM: An introduction to concept mapping every bit a participatory public health research methodology. Qual Health Res. 2005, 15: 1392-1410. 10.1177/1049732305278876.

-

Trochim WM, Cook JA, Setze RJ: Using concept mapping to develop a conceptual framework of staff's views of a supported employment programme for individuals with severe mental affliction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994, 62: 766-775.

-

Concept Systems: The Concept System software®. Ithaca, NY. 2007, 4.147

-

Kane M, Trochim W: Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. 2007, Chiliad Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc

-

Trochim WMK, Stillman FA, Clark PI, Schmitt CL: Development of a model of the tobacco industry'south interference with tobacco control programmes. Tob Control. 2003, 12: 140-147. 10.1136/tc.12.2.140.

-

Cohen J: Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 1988, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 2

-

Aarons G, Sawitzky A: Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on piece of work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006, 33: 289-301. ten.1007/s10488-006-0039-1.

-

Domino ME, Norton EC, Morrissey JP, Thakur North: Price Shifting to Jails afterwards a Alter to Managed Mental Wellness Care. Health Serv Res. 2004, 39: 1379-1402. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00295.10.

-

Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Chorpita BF, Hoagwood K, Landsverk J, Weisz JR: Cultural exchange and implementation of evidence-based practices. Res Social Work Prac. 2009, xix: 602-612. 10.1177/1049731509335529.

-

Proctor Due east, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons 1000, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M: Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research questions. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011, 38: 65-76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-seven.

-

Aarons GA, Brown SA, Hough RL, Garland AF, Wood PA: Prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders beyond five sectors of care. J Am Acad Kid Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001, 40: 419-426. 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00010.

-

Checkland K, Harrison S, Marshall M: Is the metaphor of'barriers to change'useful in agreement implementation? Evidence from general medical exercise. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007, 12: 95-ten.1258/135581907780279657.

-

Checkland Thousand, Coleman A, Harrison Southward, Hiroeh U: 'Nosotros can't become anything done because...': making sense of'barriers' to Practice-based Commissioning. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009, xiv: 20-ten.1258/jhsrp.2008.008043.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.s. National Constitute of Mental Wellness grant numbers MH070703 (PI: Aarons) and MH074678 (PI: Landsverk) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grant number CE001556 (PI: Aarons). The authors thank the customs stakeholders who participated in this study.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Gregory A. Aarons is an Associate Editor of Implementation Science. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GA contributed to the theoretical groundwork and conceptualization of the report, nerveless the original data, and supervised the analyses in the electric current projection. AG contributed to the theoretical groundwork and conceptualization of the study and conducted the related analyses. Both GA and AG contributed to the drafting of this manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary cloth

13012_2010_410_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional File 1: Concept mapping statements by cluster. List of each of the statements and their corresponding clusters created as a result of the concept mapping process. (DOC 33 KB)

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Fundamental Ltd. This is an Open Access commodity distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/ii.0), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this commodity

Cite this article

Greenish, A.E., Aarons, G.A. A comparing of policy and straight do stakeholder perceptions of factors affecting evidence-based practice implementation using concept mapping. Implementation Sci six, 104 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-vi-104

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-104

Keywords

- Stakeholder Group

- Blueprint Lucifer

- Public Mental Health Arrangement

- Direct Practice

- Public Mental Health Service

Source: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-6-104

Posted by: amesbeferal.blogspot.com

0 Response to "When Considering A Practice Change, Why Is Identification Of Stakeholders Important?"

Post a Comment